Brain-Computer Interfaces: The Neural Revolution

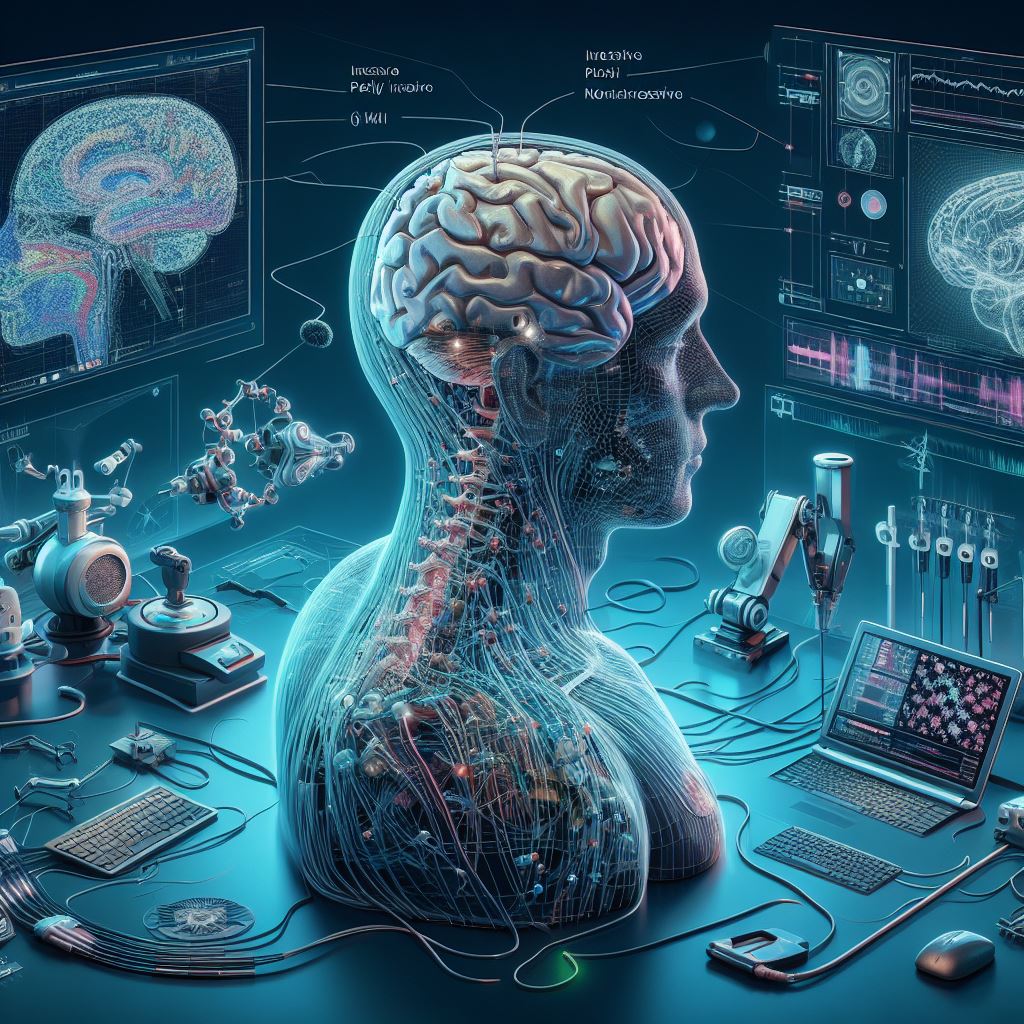

The convergence of neuroscience and technology stands at the threshold of fundamentally transforming human capabilities and experiences. Neurotechnology, particularly brain-computer interfaces, represents one of the most profound technological frontiers humanity has ever approached. These systems create direct communication pathways between the brain and external devices, bypassing traditional neuromuscular channels to enable thought-controlled interaction with machines. From restoring mobility to paralyzed individuals to enhancing cognitive capabilities and creating entirely new forms of human-machine interaction, neurotechnology promises to redefine the boundaries of human potential while raising profound ethical, social, and philosophical questions about the nature of consciousness, identity, and what it means to be human.

Understanding Brain-Computer Interface Technology

Brain-computer interfaces, commonly abbreviated as BCIs, establish direct communication channels between neural activity in the brain and external computational systems. These remarkable devices interpret electrical signals generated by neurons, translate them into commands, and enable control of external devices through thought alone.

The human brain contains approximately 86 billion neurons, each capable of generating electrical impulses that propagate through neural networks. When we think, perceive, or intend to move, specific patterns of neural activity emerge. BCIs detect these patterns using various sensor technologies, process the signals through sophisticated algorithms, and convert them into actionable commands for computers, prosthetic limbs, communication systems, or other external devices.

This technology operates on the principle that distinct mental states and intentions produce characteristic neural signatures. Through machine learning and signal processing, BCI systems learn to recognize these signatures and associate them with specific commands or outputs. Over time and with practice, users develop increasing proficiency at generating clear, distinguishable neural patterns that the system can reliably interpret.

The field encompasses a spectrum of approaches, from non-invasive techniques that monitor brain activity from outside the skull to implanted electrodes that directly record from individual neurons. Each approach offers different tradeoffs between signal quality, invasiveness, practicality, and potential applications.

Types and Approaches to Neural Interfaces

Neurotechnology encompasses diverse methodologies for interfacing with the brain, each with distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations.

A. Non-Invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces

Non-invasive BCIs monitor brain activity without penetrating the skull, offering the safest and most accessible approach to neural interfacing. Electroencephalography (EEG) represents the most widely used non-invasive technique, employing electrodes placed on the scalp to detect electrical activity from large populations of neurons firing synchronously.

EEG-based BCIs can detect various neural signals including event-related potentials triggered by specific stimuli, sensorimotor rhythms associated with movement intention or imagery, and steady-state visual evoked potentials generated by flickering visual stimuli. These systems enable applications from wheelchair control to computer cursor navigation and simple communication.

Other non-invasive approaches include functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), which measures blood oxygenation changes related to neural activity, and magnetoencephalography (MEG), which detects magnetic fields produced by electrical currents in neurons. Each technique offers different spatial and temporal resolution characteristics suited to particular applications.

B. Partially Invasive Neural Interfaces

Partially invasive approaches involve surgical placement of electrodes on the brain’s surface beneath the skull but above the neural tissue itself. Electrocorticography (ECoG) exemplifies this approach, positioning electrode arrays directly on the cortical surface to record brain activity with higher spatial resolution and signal quality than scalp-based methods while avoiding direct tissue penetration.

ECoG provides superior signal-to-noise ratios compared to EEG while presenting lower infection risks and tissue damage compared to fully invasive approaches. This intermediate position makes ECoG attractive for long-term BCI applications requiring reliable performance without the highest-risk invasive procedures.

C. Invasive Neural Interfaces

Fully invasive BCIs involve implanting electrodes directly into brain tissue, enabling recording from individual neurons or small neural populations. These intracortical interfaces provide the highest quality signals with exceptional spatial and temporal resolution, enabling more sophisticated control and information extraction.

Microelectrode arrays containing hundreds of tiny electrodes can monitor activity from numerous neurons simultaneously, capturing rich neural information that enables intuitive control of robotic limbs, detailed communication, and potentially cognitive enhancement applications. Companies and research institutions are developing increasingly sophisticated implantable devices with thousands of recording channels.

The primary tradeoffs involve surgical risks, immune responses that can degrade signal quality over time, and potential complications from chronic implants. Ongoing research addresses these challenges through improved materials, miniaturized electronics, and better understanding of long-term brain-implant interactions.

D. Bidirectional Neural Interfaces

Advanced systems go beyond simply reading neural signals to also stimulate the nervous system, creating bidirectional communication. These interfaces can both extract information from the brain and deliver sensory feedback or therapeutic stimulation. Bidirectional BCIs enable prosthetic limbs that restore not just movement but also tactile sensation, creating more natural and intuitive artificial limb control.

Neural stimulation applications extend to treating neurological conditions through deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy management, depression treatment, and potentially memory enhancement or cognitive therapy.

Medical Applications Transforming Lives

Neurotechnology’s most immediate and profound impacts manifest in medical applications that restore lost functions and treat previously intractable conditions.

A. Restoring Communication for Locked-In Patients

Perhaps no application demonstrates neurotechnology’s humanitarian potential more powerfully than restoring communication to individuals with locked-in syndrome or severe paralysis who cannot speak or move but retain cognitive function. BCI systems enable these individuals to select letters, form words, and communicate thoughts by detecting neural patterns associated with attention, intention, or imagined movements.

Recent breakthrough demonstrations have shown individuals with paralysis using BCIs to type messages at speeds approaching natural conversation, select objects on screens, and control communication software through thought alone. These systems transform lives by reconnecting isolated individuals with loved ones and the wider world.

Advanced systems are progressing toward direct speech decoding, where BCIs interpret neural activity in speech-related brain regions to reconstruct intended words without requiring letter-by-letter selection. This approach promises more natural, rapid communication that could eventually approach conversational speeds.

B. Prosthetic Control and Mobility Restoration

For individuals with limb loss or paralysis, neural interfaces enable remarkably intuitive prosthetic control. Rather than learning to operate artificial limbs through preserved muscle signals or mechanical switches, users can control prosthetics directly with the same neural signals they would naturally use to move biological limbs.

Advanced prosthetic arms controlled via BCIs enable users to perform complex manipulation tasks including grasping objects with appropriate force, manipulating tools, and even playing musical instruments. The control feels increasingly natural as users develop proficiency and as systems improve at interpreting nuanced neural commands.

Research into restoring walking through BCI-controlled exoskeletons or functional electrical stimulation of paralyzed muscles promises to return mobility to individuals with spinal cord injuries. Early demonstrations have shown proof-of-concept for this approach, with continued development aimed at making such systems practical for daily use.

C. Sensory Restoration

Bidirectional neural interfaces restore not just motor control but also sensory perception. Cochlear implants, which stimulate the auditory nerve to restore hearing, represent the most successful neural interface to date with hundreds of thousands of users worldwide. These devices demonstrate that artificial sensory input can be meaningfully integrated into neural processing.

Visual prostheses aim to restore vision to blind individuals by stimulating visual processing areas with patterns corresponding to camera-captured images. While current systems provide limited resolution, they enable basic navigation and object recognition with ongoing development toward higher-resolution perception.

Tactile feedback systems for prosthetic limbs deliver pressure and touch sensations through neural stimulation, enabling users to feel what their artificial limbs contact. This sensory restoration dramatically improves manipulation capabilities and creates more natural limb perception.

D. Neurological Disorder Treatment

Deep brain stimulation exemplifies therapeutic neural interface applications, delivering electrical pulses to specific brain regions to treat movement disorders, epilepsy, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression. Responsive systems that monitor neural activity and deliver stimulation only when needed show promise for more effective seizure control with fewer side effects.

Emerging applications explore using BCIs to detect early signs of epileptic seizures before they fully manifest, potentially enabling intervention that prevents seizure occurrence. Memory-related disorders might benefit from precisely timed stimulation that strengthens memory formation or recall processes.

Cognitive Enhancement and Human Augmentation

Beyond medical applications, neurotechnology raises tantalizing possibilities for enhancing normal human cognitive capabilities.

A. Attention and Focus Enhancement

BCIs that monitor attention levels could provide real-time feedback helping users maintain focus during cognitively demanding tasks. By detecting when attention wanes, these systems might trigger interventions—brief breaks, environmental adjustments, or reminders—that optimize sustained concentration.

Neurofeedback training using BCI systems teaches users to voluntarily modulate their brain states, potentially enhancing meditation practices, stress management, or achieving optimal cognitive states for different activities.

B. Memory Augmentation

Theoretical applications include neural interfaces that augment memory by detecting optimal moments for information encoding and delivering precisely timed stimulation that strengthens memory formation. External memory systems interfaced directly with neural circuits could provide augmented recall capabilities or even share memories between individuals.

While such applications remain largely speculative, research into the neural basis of memory formation and recall provides foundations for these possibilities. Ethical considerations around identity, authenticity of experience, and cognitive equality accompany such profound augmentation scenarios.

C. Learning Acceleration

BCIs might accelerate skill acquisition by monitoring neural activity during learning, identifying optimal training states, and providing feedback that guides learners toward more effective practice strategies. By detecting when neural circuits are most receptive to new information, systems could optimize timing and presentation of educational content.

More speculatively, direct neural stimulation patterns might eventually enable “downloading” skills or knowledge, though current understanding suggests learning involves complex neural reorganization that cannot simply be imposed through stimulation patterns.

D. Direct Brain-to-Brain Communication

Experimental demonstrations have achieved rudimentary brain-to-brain communication where one person’s neural activity, detected via BCI, triggers stimulation in another person’s brain, conveying simple information like directional cues or binary signals. While primitive, these demonstrations hint at future possibilities for direct neural communication bypassing language entirely.

Such technology raises profound questions about privacy, consent, and the boundaries between individual minds. The philosophical implications of potentially shared consciousness or merged cognitive processes challenge fundamental assumptions about individual identity and autonomy.

Consumer Applications and Entertainment

Neurotechnology is beginning to move beyond medical and research settings into consumer applications and entertainment.

A. Gaming and Virtual Reality Integration

Gaming represents an accessible entry point for consumer BCI technology. Neural interfaces enable games controlled partially or entirely through thought, creating novel gameplay mechanics impossible with traditional controllers. Players might control characters, manipulate virtual objects, or navigate environments using mental commands alongside conventional inputs.

Integration with virtual reality promises deeply immersive experiences where thoughts directly influence virtual worlds. Detecting emotional states or cognitive load could enable games that dynamically adjust difficulty, pacing, or narrative elements to optimize engagement and challenge.

B. Meditation and Wellness Applications

Consumer BCI devices targeting meditation and wellness monitor brain states associated with relaxation, focus, or meditative states, providing real-time feedback that guides users toward desired mental states. These systems gamify meditation practice through progress tracking and achievement systems that motivate consistent practice.

Sleep monitoring BCIs track brain activity patterns during rest, providing insights into sleep quality and potentially delivering interventions like targeted audio stimuli during specific sleep stages to enhance restorative processes.

C. Creative Expression Tools

Artists and musicians are exploring neural interfaces as new creative instruments. BCIs that translate mental states or emotional valence into visual art, music generation, or other creative outputs enable novel forms of expression. While current implementations remain exploratory, they demonstrate neurotechnology’s potential for enriching human creativity.

D. Productivity and Focus Tools

Consumer devices monitoring attention levels and cognitive load could optimize work environments, notification delivery, and task scheduling around detected mental states. Systems might defer interruptions when deep focus is detected or suggest breaks when cognitive fatigue emerges.

While these applications seem benign, they raise workplace surveillance concerns and questions about cognitive autonomy when neural monitoring becomes normalized in professional contexts.

Technical Challenges and Engineering Hurdles

Despite remarkable progress, significant technical challenges must be overcome for neurotechnology to reach its full potential.

A. Signal Quality and Stability

Recording high-quality neural signals consistently over extended periods presents substantial challenges. Invasive electrodes can trigger immune responses that encapsulate them in scar tissue, degrading signal quality over months or years. Non-invasive approaches struggle with low signal-to-noise ratios and limited spatial resolution.

Developing materials and electrode designs that maintain stable interfaces with neural tissue over decades remains a critical research priority. Biological compatibility, chronic stability, and minimizing tissue damage require innovative materials science and bioengineering solutions.

B. Power and Wireless Communication

Implanted devices require power sources and data transmission capabilities without continuous wired connections. Wireless power transfer and battery technologies must provide sufficient energy for sophisticated signal processing and transmission while remaining safely implanted over long periods.

Data bandwidth presents challenges as systems scale to thousands or millions of recording channels. Transmitting this data wirelessly while managing heat generation and power consumption requires advanced engineering solutions.

C. Signal Processing and Decoding

Extracting meaningful information from complex, high-dimensional neural data requires sophisticated signal processing and machine learning algorithms. These systems must operate with low latency for real-time control applications while adapting to changing neural signals over time as brain activity patterns naturally drift.

Developing decoding algorithms that generalize across individuals, require minimal calibration, and remain robust to neural signal variability represents ongoing research challenges. Advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning continue improving decoding capabilities.

D. Miniaturization and Biocompatibility

Creating fully implantable systems with all necessary electronics, power sources, and communication capabilities within biocompatible packages small enough for practical implantation requires continued miniaturization. Devices must withstand the harsh biological environment while avoiding toxic materials or immune responses.

Ethical Considerations and Societal Implications

Neurotechnology raises profound ethical questions that society must grapple with as these technologies advance.

A. Privacy and Mental Autonomy

If devices can read neural activity, what protections prevent unauthorized access to our thoughts, intentions, or mental states? Neural privacy represents a new frontier requiring legal frameworks and technical safeguards. The concept of “cognitive liberty”—the right to mental self-determination—becomes central as technologies capable of monitoring or influencing neural activity proliferate.

Questions emerge about whether neural data should receive special protection beyond ordinary medical information, who owns recorded neural data, and whether individuals can truly consent to neural monitoring given the difficulty understanding what information might be extracted.

B. Identity and Authentication

Neural interfaces that augment memory or cognition raise questions about personal identity. If memories can be modified or enhanced, what constitutes authentic experience? If cognitive capabilities depend on external systems, how does that affect our sense of self?

Authentication concerns arise if neural patterns become biometric identifiers. Unlike passwords, neural signatures cannot be changed if compromised, creating unique security challenges.

C. Equality and Access

Will cognitive enhancement technologies exacerbate inequality, creating cognitive divisions between enhanced and unenhanced individuals? If neurotechnology provides competitive advantages in education or employment, ensuring equitable access becomes crucial for preventing new forms of discrimination and stratification.

Medical neurotechnology cost and availability raise justice concerns. Should society guarantee access to basic restorative neural interfaces while potentially restricting enhancement applications? Where should lines be drawn between therapeutic and enhancement uses?

D. Regulation and Safety

How should neurotechnology be regulated given unprecedented capabilities and risks? Existing medical device frameworks may prove inadequate for devices that directly interface with and potentially modify neural function.

Long-term safety data requirements must be balanced against patient needs for access to potentially life-changing interventions. International coordination is necessary given neurotechnology’s global development and profound implications.

Current State of the Industry

Neurotechnology development spans academic research, medical device companies, and ambitious startups pursuing various approaches and applications.

A. Leading Research Institutions

Universities and research centers worldwide conduct fundamental neuroscience research underpinning BCI development. These institutions explore neural coding principles, develop new electrode technologies, and conduct clinical trials demonstrating medical applications.

Collaborative efforts between neuroscientists, engineers, clinicians, and ethicists drive progress while addressing safety and ethical considerations. Government funding agencies support this research recognizing neurotechnology’s transformative potential.

B. Medical Device Companies

Established medical device manufacturers are developing clinical-grade neural interface systems for specific medical applications. These companies navigate regulatory pathways, conduct clinical trials, and work toward commercializing safe, effective devices for treating neurological conditions.

The regulatory experience and manufacturing capabilities these companies bring enable translation of research demonstrations into practical medical devices that can reach patients through approved channels.

C. Ambitious Startups

High-profile startups are pursuing aggressive timelines for developing advanced neural interface systems. Some focus on creating high-bandwidth brain implants for medical applications and eventual enhancement uses. Others develop non-invasive consumer devices targeting wellness and productivity applications.

These ventures attract substantial investment reflecting widespread belief in neurotechnology’s transformative potential. While ambitious goals sometimes outpace current capabilities, these efforts drive rapid progress and public awareness.

D. Technology Giants

Major technology companies are investing in neurotechnology research, recognizing potential applications in computing interfaces, accessibility, and future interaction paradigms. These corporations bring substantial resources, engineering expertise, and potential distribution channels that could accelerate commercialization.

The Path Forward

Realizing neurotechnology’s promise while managing its risks requires continued scientific progress, thoughtful regulation, and societal dialogue.

A. Scientific and Engineering Advances

Continued neuroscience research deepening understanding of neural coding, circuit function, and brain organization provides foundations for more sophisticated interfaces. Engineering innovations in materials, electronics, and algorithms enable practical implementations of scientific insights.

Interdisciplinary collaboration between neuroscientists, engineers, clinicians, ethicists, and social scientists ensures development considers scientific, technical, medical, and societal dimensions.

B. Regulatory Framework Development

Adaptive regulatory frameworks must ensure safety and efficacy while enabling innovation. International coordination harmonizes standards and prevents regulatory arbitrage where companies pursue development in jurisdictions with lax oversight.

Stakeholder engagement including patients, advocacy groups, ethicists, and industry representatives shapes regulations balancing protection with access and innovation.

C. Ethical Guidelines and Public Dialogue

Professional societies, ethics boards, and public forums must establish norms and guidelines for responsible neurotechnology development and use. These discussions should engage diverse perspectives including those from different cultural, religious, and philosophical traditions.

Public education about neurotechnology capabilities, limitations, and implications enables informed societal choices about which applications to pursue and how to govern them.

D. Equitable Access Strategies

Proactive planning for equitable access prevents neurotechnology from exacerbating existing inequalities. This might include public funding for medical applications, price regulations, open-source development approaches, or other mechanisms ensuring broad benefit distribution.

Embracing the Neural Frontier Responsibly

Brain-computer interfaces represent one of humanity’s most audacious technological endeavors—directly connecting our biological neural networks with artificial computational systems. The potential benefits are extraordinary: restoring lost functions to millions with paralysis or sensory impairments, treating neurological conditions that devastate lives, and potentially enhancing human cognitive capabilities in ways currently difficult to imagine.

Yet this powerful technology demands profound responsibility. As we develop capabilities to read and potentially influence neural activity, we must vigilantly protect mental privacy, autonomy, and human dignity. The philosophical questions raised about identity, consciousness, and what it means to be human require careful consideration alongside technical development.

The path forward requires balancing optimism about neurotechnology’s promise with realism about current limitations and challenges. Overpromising creates false hope while potentially diverting resources from achievable near-term applications with proven benefits. Thoughtful, incremental progress grounded in solid science and guided by ethical principles offers the surest path to realizing benefits while managing risks.

Neurotechnology’s ultimate impact depends on choices made today by researchers, companies, regulators, and society. By prioritizing medical applications that restore lost functions, maintaining robust safety standards, protecting neural privacy and autonomy, ensuring equitable access, and fostering transparent public dialogue, we can guide this powerful technology toward enhancing human flourishing rather than creating new forms of inequality or control.

The convergence of brain and machine marks a pivotal moment in human history. How we navigate this transition will shape not just technological capabilities but fundamental aspects of human experience, society, and perhaps consciousness itself. Approached with wisdom, humility, and commitment to human dignity, neurotechnology could help millions suffering from neurological conditions while expanding human potential in ways that benefit all humanity.